Twelve-volt systems are often selected because they appear forgiving. The voltage is familiar, components are readily available, and early testing usually shows acceptable behavior. Problems tend to emerge later, once systems are operated for longer periods, under varying loads, or in less controlled environments. At that point, issues such as overheating, inconsistent performance, or shortened component life begin to surface.

In many cases, these problems are not caused by defective parts or wiring errors. They stem from the way power is controlled. Simple switching methods that apply full power or none at all struggle to support modern 12V systems that operate continuously, drive variable loads, or require predictable behavior. Recognizing when a system has outgrown basic control is essential for preventing avoidable failures.

The indicators below reflect recurring patterns seen in real-world low-voltage systems where smarter current and speed control becomes necessary.

Current behavior no longer matches system demands

Current flow in a 12V system determines how much heat is generated, how components age, and how stable operation remains over time. When loads behave dynamically but power delivery remains static, mismatches develop between what the system supplies and what the load actually needs.

Systems that transition to proportional control methods, such as those described in a 12v 8amp Pwm Controller overview, address this mismatch by adjusting power delivery instead of forcing loads to tolerate abrupt changes. This shift is often triggered by one or more of the indicators below.

Why current control becomes critical as systems mature

As usage increases, assumptions made during early design lose validity.

- Loads operate closer to their limits

- Duty cycles extend beyond initial expectations

- Thermal margins shrink quietly

Smarter control compensates for these changes rather than fighting them.

1. Components run noticeably hotter over time

One of the clearest indicators is a gradual rise in operating temperature. Components that were previously warm to the touch become uncomfortably hot after extended runtime, even though electrical parameters appear unchanged.

This usually points to inefficient power delivery rather than insufficient capacity.

What rising temperatures are really signaling

Heat reflects how power is managed, not just how much power is used.

- Excess current flows during partial load

- Switching events create repeated thermal spikes

- Heat accumulates faster than it dissipates

When temperature rise is steady rather than sudden, control behavior is often the root cause.

2. Motors or fans behave inconsistently at different loads

In systems driving motors, fans, or pumps, inconsistent speed or torque is a common warning sign. Devices may surge on startup, slow unexpectedly under minor load changes, or oscillate between speeds.

These behaviors indicate that binary control cannot adapt to real operating conditions.

Why inconsistency points to control limitations

Mechanical loads rarely behave as fixed values.

- Friction changes with wear and temperature

- Back pressure varies with operating conditions

- Startup and steady-state needs differ

Smarter speed control aligns electrical input with mechanical reality.

3. Frequent on–off cycling replaces stable operation

Systems that rely on simple switching often compensate for lack of regulation by cycling rapidly between on and off states. This approach attempts to approximate proportional behavior through repetition.

While this may appear effective, it introduces new stresses.

How excessive cycling creates hidden damage

Repeated transitions accelerate wear.

- Inrush current occurs with every restart

- Thermal cycling fatigues materials

- Contacts and switching elements erode

If cycling frequency increases as loads change, control sophistication is insufficient.

4. Failures correlate with runtime rather than load size

When failures appear only after extended operation, even at moderate load levels, thermal and control-related issues are likely involved. Systems may work reliably for short periods but degrade after hours of continuous use.

This pattern is often misdiagnosed as random failure.

Why time-based failures implicate control strategy

Electrical limits are rarely exceeded instantly.

- Heat accumulates gradually

- Component characteristics drift with temperature

- Margins erode without visible warning

Smarter current control stabilizes conditions rather than allowing slow degradation.

5. Adjustments feel coarse or unpredictable

Another indicator appears during tuning or adjustment. Small changes to a control input produce large changes in behavior, making fine control difficult or impossible. Operators compensate through trial and error rather than predictable adjustment.

This lack of resolution reflects binary or poorly modulated power delivery.

Practical consequences of coarse control

Poor resolution affects both performance and reliability.

- Motors experience mechanical shock

- Thermal loads overshoot target conditions

- Repeatability suffers

When adjustment becomes guesswork, control capability has been exceeded.

Why simple control methods reach their limits

On–off control was effective when loads were oversized, duty cycles were short, and thermal margins were generous. Modern systems operate with tighter constraints, longer runtimes, and higher expectations for consistency.

As a result, limitations that were once negligible now dominate system behavior.

How modern operating conditions change requirements

- Continuous operation replaces intermittent use

- Compact designs limit heat dissipation

- Variable loads replace fixed assumptions

These changes demand proportional rather than binary control.

The relationship between current control and heat

Heat generation in electrical systems is governed by current flow and resistance. Even small inefficiencies produce significant thermal effects when sustained over time. Poor control amplifies these effects by delivering excess current when it is not needed.

Understanding this relationship reframes overheating as a control issue rather than a component defect.

A general explanation of how electrical losses convert into heat and how heat moves through systems is outlined in Wikipedia’s article on heat transfer, which describes conduction, convection, and radiation as the primary mechanisms affecting thermal behavior.

These principles apply directly to low-voltage systems.

Smarter speed control reduces mechanical stress

For rotating equipment, smoother speed regulation reduces mechanical wear. Abrupt starts, stops, and speed changes strain bearings, shafts, and couplings.

Proportional control aligns electrical input with mechanical response.

Mechanical benefits of smoother control

- Reduced torque spikes

- Lower vibration levels

- More predictable wear patterns

These benefits extend service life beyond electrical components alone.

When current headroom is not the real issue

A common response to overheating or instability is selecting higher-rated components. While additional capacity can help, it does not address inefficient power delivery.

Systems may still run hot even with oversized components.

Why oversizing alone fails

- Inefficiencies remain unchanged

- Heat generation shifts rather than disappears

- Control behavior stays coarse

Improving control often yields greater reliability than increasing ratings.

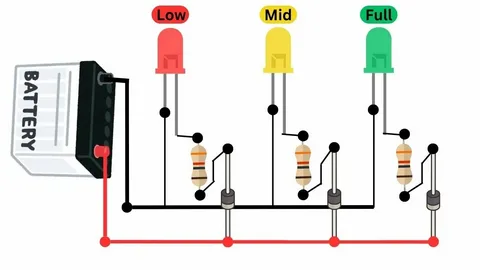

Diagnostic value of thermal behavior

Temperature trends offer insight into control adequacy. Systems with appropriate current regulation reach a stable thermal equilibrium. Those with poor control continue heating until failure or shutdown occurs.

Monitoring thermal behavior helps distinguish between capacity and control problems.

Signs of inadequate control in temperature data

- Continuous temperature rise under steady load

- Hotspots near switching elements

- Large temperature swings during operation

These patterns point toward control refinement rather than component replacement.

Transitioning toward smarter control

Recognizing the indicators is the first step. The next is evaluating how power is delivered relative to load behavior. This often leads to adopting control methods that adjust current and speed proportionally.

Smarter control does not eliminate heat or stress, but it distributes them more evenly and predictably.

Practical outcomes of improved control

- Lower peak temperatures

- Reduced cycling and inrush events

- More stable system behavior

These outcomes compound over time.

Why control strategy shapes system lifespan

Electrical systems rarely fail at their rated limits. They fail at their weakest points after repeated stress. Control strategy determines where that stress concentrates.

Systems with proportional control age evenly. Those with binary control fail locally and unexpectedly.

Closing perspective: indicators precede failures

The need for smarter current and speed control in a 12V system rarely arrives without warning. Rising temperatures, inconsistent behavior, excessive cycling, time-dependent failures, and coarse adjustment all signal that control methods no longer match operational reality.

Addressing these indicators early shifts system behavior from reactive to stable. Instead of compensating for inefficiencies with larger components or added cooling, smarter control aligns power delivery with real demand. In low-voltage systems, this alignment is often the difference between ongoing reliability and a pattern of quiet, repeated failure.